What Was the Preferred Art Form for Early Christians

Early Christian art and architecture or Paleochristian fine art is the art produced by Christians or under Christian patronage from the earliest catamenia of Christianity to, depending on the definition used, old between 260 and 525. In practice, identifiably Christian art just survives from the second century onwards.[1] Later on 550 at the latest, Christian art is classified equally Byzantine, or of some other regional type.[1] [two]

It is hard to know when distinctly Christian fine art began. Prior to 100, Christians may have been constrained by their position as a persecuted group from producing durable works of art. Since Christianity was largely a religion not well represented in the public sphere,[ citation needed ] the lack of surviving art may reflect a lack of funds for patronage, and simply minor numbers of followers. The Quondam Testament restrictions against the production of graven (an idol or fetish carved in woods or stone) images (run into also Idolatry and Christianity) may also have constrained Christians from producing fine art. Christians may take made or purchased art with infidel iconography, but given it Christian meanings, every bit they after did. If this happened, "Christian" art would non be immediately recognizable as such.

Early on Christianity used the same creative media as the surrounding pagan civilization. These media included fresco, mosaics, sculpture, and manuscript illumination. Early on Christian art used not but Roman forms but also Roman styles. Tardily classical manner included a proportional portrayal of the human being torso and impressionistic presentation of space. Late classical style is seen in early Christian frescos, such every bit those in the Catacombs of Rome, which include nigh examples of the earliest Christian art.[iii] [4] [v]

Early Christian art and architecture adapted Roman creative motifs and gave new meanings to what had been pagan symbols. Among the motifs adopted were the peacock, Vitis viniferavines, and the "Good Shepherd". Early Christians also developed their own iconography; for example, such symbols as the fish (ikhthus) were not borrowed from heathen iconography.

Early Christian art is generally divided into 2 periods by scholars: before and after either the Edict of Milan of 313, bringing the then-called Triumph of the Church under Constantine, or the First Quango of Nicea in 325. The earlier period being called the Pre-Constantinian or Ante-Nicene Period and afterward being the menstruation of the Beginning 7 Ecumenical Councils.[6] The end of the flow of early on Christian fine art, which is typically defined by art historians as being in the fifth–7th centuries, is thus a good bargain later than the end of the period of early Christianity as typically defined by theologians and church historians, which is more ofttimes considered to end under Constantine, around 313–325.

Symbols [edit]

During the persecution of Christians nether the Roman Empire, Christian fine art was necessarily and deliberately furtive and ambiguous, using imagery that was shared with pagan civilization but had a special meaning for Christians. The earliest surviving Christian fine art comes from the tardily 2d to early 4th centuries on the walls of Christian tombs in the catacombs of Rome. From literary show, in that location may well accept been panel icons which, similar about all classical painting, have disappeared. Initially Jesus was represented indirectly by pictogram symbols such as the Ichthys (fish), peacock, Lamb of God, or an ballast (the Labarum or Chi-Rho was a later development). Afterwards personified symbols were used, including Jonah, whose three days in the belly of the whale pre-figured the interval between the expiry and resurrection of Jesus, Daniel in the lion's den, or Orpheus' charming the animals. The paradigm of "The Good Shepherd", a beardless youth in pastoral scenes collecting sheep, was the near common of these images, and was probably not understood as a portrait of the historical Jesus.[vii] These images acquit some resemblance to depictions of kouros figures in Greco-Roman art. The "most total absenteeism from Christian monuments of the period of persecutions of the plain, unadorned cross" except in the disguised form of the ballast,[eight] is notable. The Cross, symbolizing Jesus' crucifixion on a cross, was non represented explicitly for several centuries, possibly because crucifixion was a punishment meted out to common criminals, but likewise because literary sources noted that it was a symbol recognised every bit specifically Christian, as the sign of the cross was fabricated by Christians from very early on on.

The popular formulation that the Christian catacombs were "undercover" or had to hide their amalgamation is probably wrong; catacombs were large-scale commercial enterprises, usually sited only off major roads to the metropolis, whose existence was well known. The inexplicit symbolic nature of many early Christian visual motifs may have had a function of discretion in other contexts, but on tombs, they probably reflect a lack of any other repertoire of Christian iconography.[9]

The pigeon is a symbol of peace and purity. Information technology can be found with a halo or celestial low-cal. In one of the earliest known Trinitarian images, "the Throne of God as a Trinitarian epitome" (a marble relief carved c. 400 CE in the drove of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation), the dove represents the Spirit. It is flying to a higher place an empty throne representing God, in the throne are a chlamys (cloak) and diadem representing the Son. The Chi-Rho monogram, XP, plainly first used by Constantine I, consists of the first ii characters of the name 'Christos' in Greek.

Christian fine art before 313 [edit]

Noah praying in the Ark, from a Roman crypt

A general assumption that early Christianity was generally aniconic, opposed to religious imagery in both theory and exercise until about 200, has been challenged by Paul Corby Finney'south analysis of early Christian writing and cloth remains (1994). This distinguishes three unlike sources of attitudes affecting early Christians on the issue: "get-go that humans could accept a direct vision of God; second that they could non; and, third, that although humans could come across God they were best brash non to expect, and were strictly forbidden to represent what they had seen". These derived respectively from Greek and Virtually Eastern heathen religions, from Aboriginal Greek philosophy, and from the Jewish tradition and the Old Testament. Of the iii, Finney concludes that "overall, Israel's aversion to sacred images influenced early Christianity considerably less than the Greek philosophical tradition of invisible deity apophatically divers", then placing less emphasis on the Jewish background of nigh of the first Christians than virtually traditional accounts.[10] Finney suggests that "the reasons for the non-appearance of Christian art before 200 take zip to practice with principled aversion to art, with other-worldliness, or with anti-materialism. The truth is simple and mundane: Christians lacked land and majuscule. Art requires both. As soon as they began to acquire land and capital letter, Christians began to experiment with their own distinctive forms of art".[eleven]

In the Dura-Europos church building, of about 230–256, which is in the best status of the surviving very early churches, there are frescos of biblical scenes including a figure of Jesus, also equally Christ as the Good Shepherd. The edifice was a normal house apparently converted to utilize as a church.[12] [13] The earliest Christian paintings in the Catacombs of Rome are from a few decades earlier, and these represent the largest body of examples of Christian art from the pre-Constantinian period, with hundreds of examples decorating tombs or family tomb-chambers. Many are elementary symbols, but there are numerous figure paintings either showing orants or female person praying figures, normally representing the deceased person, or figures or shorthand scenes from the bible or Christian history.

The fashion of the catacomb paintings, and the entirety of many decorative elements, are effectively identical to those of the catacombs of other religious groups, whether conventional pagans following Ancient Roman religion, or Jews or followers of the Roman mystery religions. The quality of the painting is depression compared to the large houses of the rich, which provide the other main corpus of painting surviving from the flow, simply the shorthand depiction of figures can have an expressive charm.[fourteen] [15] [16] A like situation applies at Dura-Europos, where the decoration of the church is comparable in way and quality to that of the (larger and more lavishly painted) Dura-Europos synagogue and the Temple of Bel. At least in such smaller places, information technology seems that the available artists were used by all religious groups. It may also take been the case that the painted chambers in the catacombs were busy in similar style to the best rooms of the homes of the better-off families cached in them, with Christian scenes and symbols replacing those from mythology, literature, paganism and eroticism, although we lack the evidence to ostend this.[17] [eighteen] [nineteen] We do have the same scenes on modest pieces in media such as pottery or glass,[xx] though less oftentimes from this pre-Constantinian period.

There was a preference for what are sometimes chosen "abbreviated" representations, small groups of say one to four figures forming a unmarried motif which could exist hands recognised as representing a particular incident. These vignettes fitted the Roman style of room ornamentation, gear up in compartments in a scheme with a geometrical structure (see gallery below).[21] Biblical scenes of figures rescued from mortal danger were very popular; these represented both the Resurrection of Jesus, through typology, and the salvation of the soul of the deceased. Jonah and the whale,[22] [23] the Cede of Isaac, Noah praying in the Ark (represented equally an orant in a big box, peradventure with a pigeon conveying a co-operative), Moses striking the rock, Daniel in the king of beasts's den and the Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace ([Daniel 3:10–30]) were all favourites, that could be easily depicted.[24] [25] [21] [26] [27]

Early Christian sarcophagi were a much more expensive option, fabricated of marble and often heavily decorated with scenes in very high relief, worked with drills. Free-standing statues that are unmistakably Christian are very rare, and never very large, equally more common subjects such as the Skilful Shepherd were symbols appealing to several religious and philosophical groups, including Christians, and without context no affiliation can exist given to them. Typically sculptures, where they announced, are of rather high quality. I infrequent group that seems conspicuously Christian is known equally the Cleveland Statuettes of Jonah and the Whale,[28] [21] and consists of a group of modest statuettes of almost 270, including two busts of a young and fashionably dressed couple, from an unknown discover-spot, possibly in modern Turkey. The other figures tell the story of Jonah in 4 pieces, with a Good Shepherd; how they were displayed remains mysterious.[29]

The delineation of Jesus was well-developed by the end of the pre-Constantinian period. He was typically shown in narrative scenes, with a preference for New Testament miracles, and few of scenes from his Passion. A diversity of different types of appearance were used, including the thin long-faced figure with long centrally-parted hair that was later to become the norm. But in the primeval images as many prove a stocky and short-haired beardless figure in a short tunic, who can only exist identified by his context. In many images of miracles Jesus carries a stick or wand, which he points at the subject field of the miracle rather like a modern phase wizard (though the wand is a good bargain larger).

Saints are fairly often seen, with Peter and Paul, both martyred in Rome, by some manner the almost common in the catacombs there. Both already have their distinctive appearances, retained throughout the history of Christian art. Other saints may not exist identifiable unless labelled with an inscription. In the same way some images may correspond either the Last Supper or a contemporary agape feast.

-

-

Moses striking the stone in the desert, a prototype of baptism[31]

-

Crypt chamber with (from top): Orants, Jonah and the Whale, Moses striking the stone (left), Noah praying in the ark, Adoration of the Magi. 200–250

Christian architecture after 313 [edit]

In the 4th century, the rapidly growing Christian population, at present supported by the state, needed to build larger and grander public buildings for worship than the mostly discreet meeting places they had been using, which were typically in or among domestic buildings. Pagan temples remained in use for their original purposes for some fourth dimension and, at least in Rome, even when deserted were shunned by Christians until the sixth or 7th centuries, when some were converted to churches.[32] Elsewhere this happened sooner. Architectural formulas for temples were unsuitable, not merely for their infidel associations, but considering pagan cult and sacrifices occurred outdoors under the open up sky in the sight of the gods, with the temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury, equally a windowless properties.

The usable model at paw, when Emperor Constantine I wanted to memorialize his purple piety, was the familiar conventional architecture of the basilica. There were several variations of the bones plan of the secular basilica, ever some kind of rectangular hall, merely the ane usually followed for churches had a center nave with one aisle at each side, and an apse at one end opposite to the principal door at the other. In, and often also in forepart of, the apse was a raised platform, where the altar was placed and the clergy officiated. In secular buildings this plan was more typically used for the smaller audition halls of the emperors, governors, and the very rich than for the not bad public basilicas operation equally police courts and other public purposes.[33] This was the normal pattern used for Roman churches, and generally in the Western Empire, but the Eastern Empire, and Roman Africa, were more than adventurous, and their models were sometimes copied in the W, for example in Milan. All variations allowed natural light from windows high in the walls, a departure from the windowless sanctuaries of the temples of most previous religions, and this has remained a consistent feature of Christian church architecture. Formulas giving churches with a large key area were to become preferred in Byzantine architecture, which adult styles of basilica with a dome early on.[34]

A particular and curt-lived type of building, using the same basilican form, was the funerary hall, which was not a normal church, though the surviving examples long agone became regular churches, and they e'er offered funeral and memorial services, but a edifice erected in the Constantinian period as an indoor cemetery on a site continued with early on Christian martyrs, such every bit a catacomb. The six examples built by Constantine outside the walls of Rome are: Old Saint Peter's Basilica, the older basilica defended to Saint Agnes of which Santa Costanza is now the only remaining element, San Sebastiano fuori le mura, San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, Santi Marcellino e Pietro al Laterano, and one in the modern park of Villa Gordiani.[35]

A martyrium was a building erected on a spot with detail significance, oft over the burial of a martyr. No item architectural form was associated with the blazon, and they were frequently small. Many became churches, or chapels in larger churches erected adjoining them. With baptistries and mausolea, their often smaller size and different function made martyria suitable for architectural experimentation.[36]

Amid the central buildings, not all surviving in their original grade, are:

- Constantinian Basilicas:

- Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran

- St Mary Major

- Quondam Saint Peter'south Basilica

- Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- Church building of the Nativity

- Saint Sofia Church, Sofia

- Centralized Programme

- Santa Constanza, congenital as an Imperial mausoleum adjoining a funerary hall, part of the wall of which survives.[37]

- Church of St. George, Sofia

Christian art after 313 [edit]

With the concluding legalization of Christianity, the existing styles of Christian art continued to develop, and accept on a more monumental and iconic character. Before long very big Christian churches began to be constructed, and the majority of the rich elite adjusted Christianity, and public and elite Christian art became grander to suit the new spaces and clients.

Although borrowings of motifs such every bit the Virgin and Child from pagan religious art had been pointed out every bit far back as the Protestant Reformation, when John Calvin and his followers gleefully used them equally a stick with which to trounce all Christian art, the belief of André Grabar, Andreas Alföldi, Ernst Kantorowicz and other early 20th-century art historians that Roman Imperial imagery was a much more significant influence "has go universally accustomed". A book by Thomas F. Mathews in 1994 attempted to overturn this thesis, very largely denying influence from Imperial iconography in favour of a range of other secular and religious influence, merely was roughly handled by academic reviewers.[38]

More circuitous and expensive works are seen, as the wealthy gradually converted, and more theological complication appears, as Christianity became field of study to acrimonious doctrinal disputes. At the same time a very different type of art is found in the new public churches that were now existence constructed. Somewhat by accident, the all-time group of survivals of these is from Rome where, together with Constantinople and Jerusalem, they were presumably at their near magnificent. Mosaic now becomes important; fortunately this survives far better than fresco, although it is vulnerable to well-meaning restoration and repair. It seems to accept been an innovation of early Christian churches to put mosaics on the wall and utilise them for sacred subjects; previously, the technique had essentially been used for floors and walls in gardens. By the end of the catamenia the fashion of using a aureate basis had developed that continued to characterize Byzantine images, and many medieval Western ones.

With more than infinite, narrative images containing many people develop in churches, and besides begin to be seen in later catacomb paintings. Continuous rows of biblical scenes announced (rather high up) along the side walls of churches. The best-preserved 5th-century examples are the set of Sometime Testament scenes along the nave walls of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. These can be compared to the paintings of Dura-Europos, and probably likewise derive from a lost tradition of both Jewish and Christian illustrated manuscripts, likewise every bit more general Roman precedents.[39] [40] The big apses contain images in an iconic fashion, which gradually developed to centre on a large figure, or after just the bust, of Christ, or later on of the Virgin Mary. The primeval apses testify a range of compositions that are new symbolic images of the Christian life and the Church.

No panel paintings, or "icons" from before the 6th century have survived in anything similar an original condition, only they were conspicuously produced, and becoming more important throughout this menses.

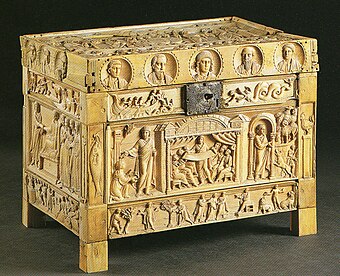

Sculpture, all much smaller than lifesize, has survived in ameliorate quantities. The about famous of a considerable number of surviving early Christian sarcophagi are perhaps the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus and Dogmatic sarcophagus of the 4th century. A number of ivory carvings take survived, including the circuitous late-5th-century Brescia Casket, probably a product of Saint Ambrose's episcopate in Milan, then the seat of the Purple courtroom, and the 6th-century Throne of Maximian from the Byzantine Italian capital of Ravenna.

- Manuscripts

- Quedlinburg Itala fragment – fifth-century Quondam Testament

- Vienna Genesis

- Rossano Gospels

- Cotton Genesis

- Late Antique mosaics in Italian republic and Early on Byzantine mosaics in the Heart E.

Aureate glass [edit]

Gold sandwich drinking glass or aureate drinking glass was a technique for fixing a layer of golden leaf with a blueprint between 2 fused layers of glass, adult in Hellenistic glass and revived in the 3rd century. There are a very fewer larger designs, simply the great majority of the around 500 survivals are roundels that are the cut-off bottoms of wine cups or spectacles used to marker and decorate graves in the Catacombs of Rome past pressing them into the mortar. The groovy majority are 4th century, extending into the 5th century. Most are Christian, but many pagan and a few Jewish, and had probably originally been given as gifts on marriage, or festive occasions such as New Year. Their iconography has been much studied, although artistically they are relatively unsophisticated.[41] Their subjects are similar to the crypt paintings, only with a departure residue including more portraiture of the deceased (usually, information technology is presumed). The progression to an increased number of images of saints tin can be seen in them.[42] The same technique began to be used for gold tesserae for mosaics in the mid-1st century in Rome, and by the 5th century these had become the standard groundwork for religious mosaics.

See also [edit]

- Oldest churches in the world

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Jensen 2000, p. 15–16.

- ^ van der Meer, F., 27 uses "roughly from 200 to 600".

- ^ Syndicus 1962, p. 10–xiv.

- ^ Syndicus 1962, p. 30-32.

- ^ Jensen 2000, p. 12-xv.

- ^ Jensen 2000, p. 16.

- ^ Syndicus 1962, p. 21-23.

- ^ Marucchi, Orazio. "Archæology of the Cross and Crucifix." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. vii Sept. 2018 online

- ^ Jensen 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Finney, 8–xii, viii and 11 quoted

- ^ Finney, 108

- ^ Weitzmann 1979, p. no. 360.

- ^ Graydon F. Snyder, Ante pacem: archaeological evidence of church building life before Constantine, p. 134, Mercer University Press, 2003, google books

- ^ Syndicus 1962, p. 29-thirty.

- ^ Jensen 2000, p. 24.

- ^ Beckwith 1979, p. 23–24.

- ^ Syndicus 1962, p. 10–11.

- ^ Jensen 2000, p. x-xv.

- ^ Balch, 183, 193

- ^ Weitzmann 1979, p. no. 377.

- ^ a b c Weitzmann 1979, p. 396.

- ^ Weitzmann 1979, p. no. 365.

- ^ Balch, 41 and chapter 6

- ^ Syndicus 1962, p. 15-18.

- ^ Jensen 2000, p. Chapte three.

- ^ Weitzmann 1979, p. no. 360-407.

- ^ Beckwith 1979, p. 21-24.

- ^ Weitzmann 1979, p. no. 362-367.

- ^ Weitzmann 1979, p. 410.

- ^ Weitzmann 1979, p. no. 383.

- ^ Weitzmann 1979, p. 424-425.

- ^ Syndicus 1962, p. 39.

- ^ Syndicus 1962, p. 40.

- ^ Syndicus 1962, chapter II, covers the whole story of the Christianization of the basilica..

- ^ Webb, Matilda. The churches and catacombs of early Christian Rome: a comprehensive guide, p. 251, 2001, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 1-902210-58-ane, ISBN 978-one-902210-58-2, google books

- ^ Syndicus 1962, chapter III.

- ^ Syndicus 1962, p. 69-70.

- ^ The book was The Clash of Gods: A Reinterpretation of Early Christian Art by Thomas F. Mathews. Review past: Westward. Eugene Kleinbauer (quoted, from p. 937), Speculum, Vol. 70, No. 4 (October., 1995), pp. 937-941, Medieval Academy of America, JSTOR; JSTOR has other reviews, all with criticisms along similar lines: Peter Chocolate-brown, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 77, No. 3 (Sep., 1995), pp. 499–502; RW. Eugene Kleinbauer, Speculum, Vol. lxx, No. iv (Oct., 1995), pp. 937–941, Liz James, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 136, No. 1096 (Jul., 1994), pp. 458–459;Annabel Wharton, The American Historical Review, Vol. 100, No. 5 (Dec., 1995), pp. 1518–1519 .

- ^ Syndicus 1962, p. 52-54.

- ^ Weitzmann 1979, p. 366-369.

- ^ Beckwith 1979, p. 25-26.

- ^ Grig, throughout

References [edit]

- Balch, David L., Roman Domestic Art & Early on Firm Churches (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Attestation Serial), 2008, Mohr Siebeck, ISBN 3161493834, 9783161493836

- Beckwith, John (1979). Early Christian and Byzantine Fine art (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN0140560335.

- Finney, Paul Corby, The Invisible God: The Earliest Christians on Art, Oxford University Press, 1997, ISBN 0195113810, 9780195113815

- Grig, Lucy, "Portraits, Pontiffs and the Christianization of 4th-Century Rome", Papers of the British Schoolhouse at Rome, Vol. 72, (2004), pp. 203–230, JSTOR

- Honour, Hugh; Fleming, J. (2005). The Visual Arts: A History (Seventh ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN0-13-193507-0.

- Jensen, Robin Margaret (2000). Understanding Early Christian Fine art. Routledge. ISBN0415204542. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013.

- van der Meer, F., Early Christian Art, 1967, Faber and Faber

- Syndicus, Eduard (1962). Early Christian Art. London: Burns & Oates. OCLC 333082.

- "Early on Christian art". In Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Weitzmann, Kurt (1979). Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Fine art.

External links [edit]

- 267 plates from Wilpert, Joseph, ed., Dice Malereien der Katakomben Roms (Tafeln)("Paintings in the Roman catacombs, (Plates)"), Freiburg im Breisgau, 1903, from Heidelberg University Library]

- Early Christian fine art, introduction from the Country University of New York at Oneonta

- CHRISTIAN CONTRIBUTION TO ART AND Architecture IN INDIA

stoddarddoely1980.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_Christian_art_and_architecture